Mette Winckelmann: The Body’s Own Agenda, 2021

Julia Bryan-Wilson

Huddled together on the ground sit nearly two hundred ceramic vessels—pitchers, jugs, bowls, platters, cups, goblets, vases. Though most stand upright, some of them have been knocked over, and the sprawling swarm resembles the aftermath of a raucous party. Diverse in shape and silhouette, the various pots and bowls are hand-glazed with deep reds and blacks and pale yellows that drip and ooze down their sides. This installation by queer Danish artist Mette Wincklemann, entitled Blood, Phlegm, and Bile, 2016, refers to medieval theories of illness, in which imbalances between the four fundamental fluids or humors (yellow bile, black bile, blood, and phlegm) were understood to be the underlying root of all disease.

In this piece, Wincklemann activates long-standing connections between ceramics and human physicality across several religious traditions—in both the Hebrew bible and the Qur’an, people are said to have been made of clay—as she also twists that analogy by relating the vulnerable curved bellies, openings, and lips of pots to their fragile bodily counterparts. Understood as proxies or surrogates for humans, the large collection of vessels on the floor looks like a gathering of unlike and easily breakable bodies, each one different in shape yet united by a distinct color palette that has been somewhat slapdash in its application. The collection has a disobedient feel, as if the pots have assembled surreptitiously to plot a rebellion. As the viewer looks down at this cluster of objects, some of their dark mouths gape open in our direction. Let’s call it a coalition of the lowly.

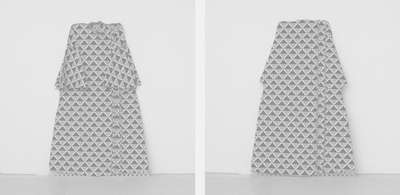

Winckelmann is well-known for her queer feminist abstractions and her extensive use of crafts across her practice– particularly the unsettled manner in which she recruits both handmade textiles and factory-fabricated fabric to gesture to non-conforming sexualities. She embarks upon a multi-pronged research process that weaves together material histories and archival sources, for example integrating slogans and buttons (“I like older women”) from New York’s Lesbian Herstory Archive into paintings that repeat but also fracture the source material until it becomes illegible.

These inter-related actions of citing, rereading, and coding are also at the heart of Winckelmann’s years-long investigations of flags. For her, flags are not only fraught national symbols but also can be marshalled for feminist and anti-racist ends quite critical of their traditional uses. She grasps how flags and cloth banners have been utilized for versatile purposes due to their flexibility, portability, and relatively accessible means of making. Her patchwork “flags of freedom” are at once invocations of protest visual culture like defiant suffragette banners as well as the subcultural queer hankie code in which “flagging” (wearing a colored handkerchief in one’s pocket) is a way to signal sexual preferences readable only to others in the community. A red hankie in the left pocket tells other men out cruising that its wearer is interested in fisting as a top (taking an active/insertive role); a yellow hankie on the right signals a desire for bottoming (playing the receptive/passive part) during water sports. As Hal Fischer explored in his 1977 conceptual photography project Gay Semiotics,

Traditional Western societies have utilized signifiers for accessibility. The wedding ring, engagement ring, lavaliere, or pin are signifiers for non-availability which are always attached to women. Signs for availability simply do not exist. In gay culture, the reverse is true. Signifiers exist for accessibility. Obviously, one reason behind this is that gays are less constrained by a type of code which defines people as property of others or feels the need to promote monogamy.

Foster’s project was limited to a discussion of gay men, yet his insights into intricate sign systems that were veiled from mainstream culture and the ways that color takes on charged meanings provide a queer framework for understanding Winckelmann’s persistent return to craft forms in which expectations are reversed.

The assortment of pots on the floor seem to offer a related kind of inversion, in which the materiality of so-called “women’s work” is not neat and orderly, as might be the expectation, but abject, unruly, and visceral. She often scrambles high and low registers of making. These goblets and platters and pitchers are cheaply produced, kitsch imitations of older items that she has purchased and then transformed with thick and luscious glazes that comingle, pool together, and stream down in rivulets like glistening tears, or spit, or pus. As she told me, “glazes are unpredictable, and ceramics are like bodies that you want to control but that exceed the limits of that control. The body has its own agenda.” The glazes are predominately red, black, and white—a triad of hues she experimented with in her series Come Undone—but they also mix to create shades of gray, flashes of yellow, and gradients of earthy pink. Glaze tones and textures are notoriously finicky and variable, and even the most seasoned ceramicist has experienced unexpected results due to the how the kiln heats and its interaction with air, the other objects around it, and environmental circumstances that might burn away carefully applied designs or blur lines that bleed together. Some of the vessels seem to leaking, with fluids welling up and spilling out of their containers; just like a body whose flesh can act with its own will and urges not always manageable by the mind, so too can the material of clay and mineral glaze have their own agenda, veering in unpredictable directions.

For Winckelmann, color is both a historical contingency (rather than universal or given, colors have specific lineages and emerge in particular times and places as collectively recognized and named) and a powerful affective tool for creating sensation. She states: “In my work, I try to always be conscious of the fact that working with colours is working with references, associations, feelings, senses. You are activating a certain atmosphere or ambiance, similar to the way a chord can fill a room and activates an emotional register in a listener.” The synesthesia she refers to—where seeing is merged with hearing in a multi-sensorial response —returns us to historical theories of the body and medicine, for medieval ideas about perception were far more integrated than are modern notions that strictly separate eye from ear or tongue.

Winckelmann’s Blood, Bile, and Phlegm was first created five years ago, but to witness it again in 2021, in the midst of the still-raging Covid-19 pandemic that as of this writing has claimed some four and a half million lives worldwide and left millions more with chronic illness, is to be reminded of the volatility of contemporary ideas about bodies, health, and human frailty. It is the piece within her large and impressive oeuvre that stands out to me in this moment the most. As I wrote in the beginning of this essay, I see these ceramics massing amongst themselves as an improvised collective: but are they dangerous in their numbers? Or do they gesture to the necessity of seeing beyond the individual and taking care of those around us as a component of social responsibility? The pots themselves refuse to say, but for me some of their shapes are reminiscent of organs (lungs and stomachs are also kinds of vessels), and their messy fluids hint at the ravages of disease with its excessive and uncontrollable nature. Every country has had its own response to this virus, and these drastically different approaches have yielded wide discrepancies among regions in terms of death counts. In the US, far-right rejections of science and the refusal of Trump followers to act responsibly by adhering to the most basic of preventative measures have been disastrous, which begs the question: are we any wiser than they were in medieval times about how the body works? About how public health functions? As with the rest of her work and her materially-grounded abstractions, Winckelmann generates ambiguities that eschew easy answers, instead letting many meanings proliferate.